An Eulogy of Claudia

clicca la foto per visualizzare la galleria

When two people love each other, they are convinced that they have always known each other. Even as children, they knew each other. It seems strange, uncanny, to me that I didn’t know Claudia when she was a child. So, I convinced myself that I did know her, but without realizing it.

When I was seven I fell into a depressive mood that led my parents to send me to a psychotherapist... I often cried at the thought that my paErents would die sooner or later. How could I have lived while they were dead? After many years I told myself that the reason for my precocious sadness lay elsewhere.

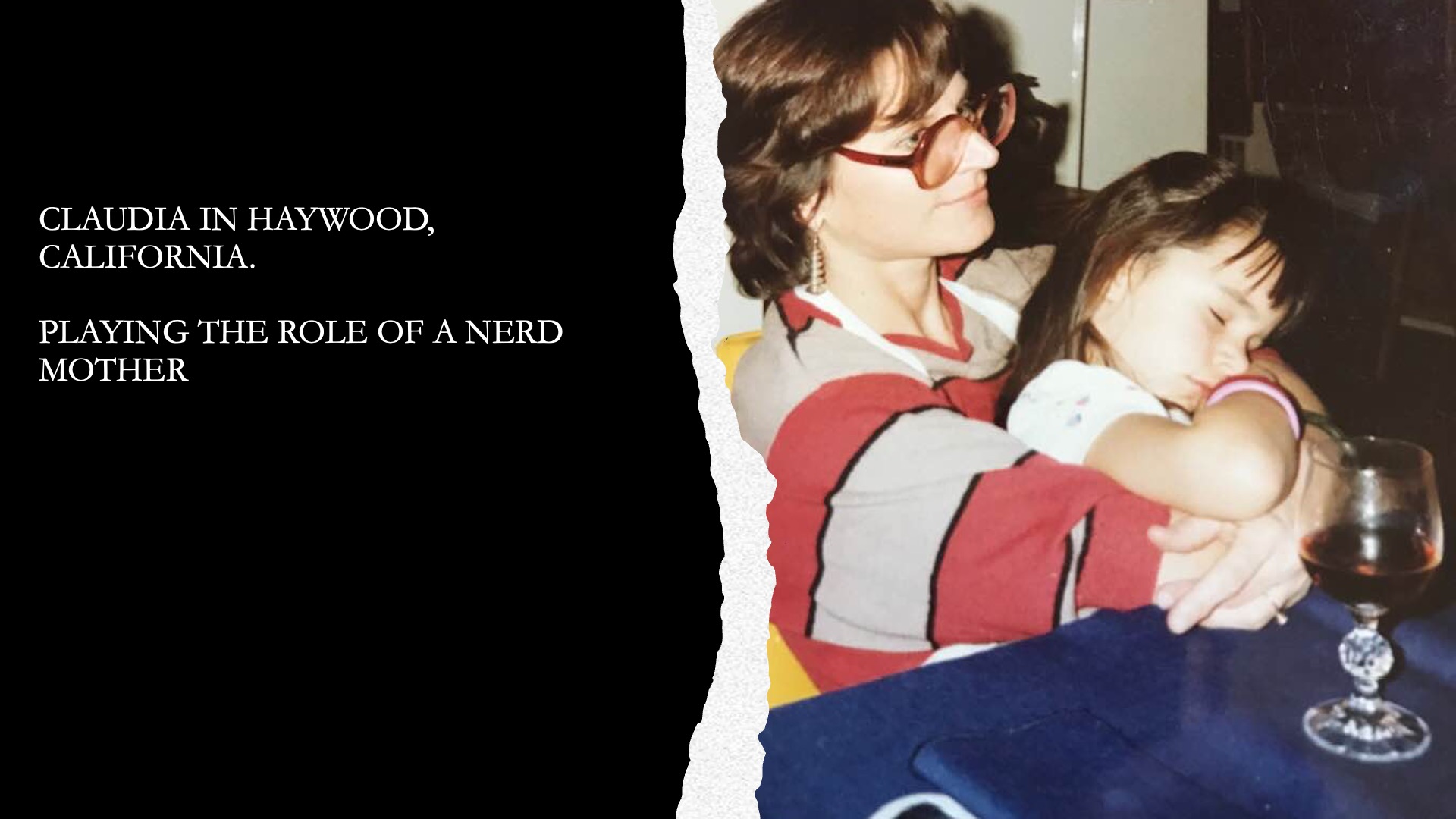

In fact, at that time, on the other side of the planet, in California, a little girl my age was suffering. The doctors had decided to remove one of her kidneys, which they did in Los Angeles, putting her in a children-only ward to which her parents had no free access. At the time, American doctors were as stupid as Italian doctors; they thought that parents would get in the way of their job of carving up children’s bodies... That child was Claudia. So, I often think: I must have known that the young girl who was to become my partner was suffering, separated from her parents. How could I not have known it? How could I not have feared death?

Claudia and I met late in life, when we were both 44; two months separate our births. The first time I went out with her, in Trastevere, I made a fool of myself. In a bar, when she asked me how old I was, I don’t know why, but I took a year off my real age; “43”, I said. But I soon gave myself away, because when Claudia asked me what my Chinese astrological sign was, I answered that I was a Mouse. “I’m a Mouse too,” she said. But Chinese astrological signs are determined according to the year of your birth. She forgave me the lie. Claudia always forgives everyone. Since then, however, I have stopped telling lies. Claudia has been my moral re-educator.

Claudia says that Americans are more ethical than Europeans at heart. Maybe she’s right, despite Trump and the Wolves of Wall Street. In fact, Claudia confessed to me one day that she has never lied. It’s impossible for her to lie; a lie would never come to her. Instead, she may omit certain important details. For example, when you ask her who she works for, she just says that she works for an obscure NGO that struggles for peace. She never says that this NGO was founded by Einstein and Russell and was awarded the Nobel Prize while she was working for it.

I began with Claudia aged 7, who was suffering, whose life was in danger. It’s the suffering side of Claudia that I would like to talk about here. Which is perhaps something scandalous, because everyone knows how radiant Claudia is, always cheerful, full of life. Claudia expresses a joie de vivre that does not carry the weight of the fear of death. She knows how to laugh even in tragedy. In 1993, as she told me that she had been diagnosed with cancer, which she would later defeat with a smile, she made the sign that in the Neapolitan language of gestures means going up to heaven; in other words, death: ------ She was mocking her illness.

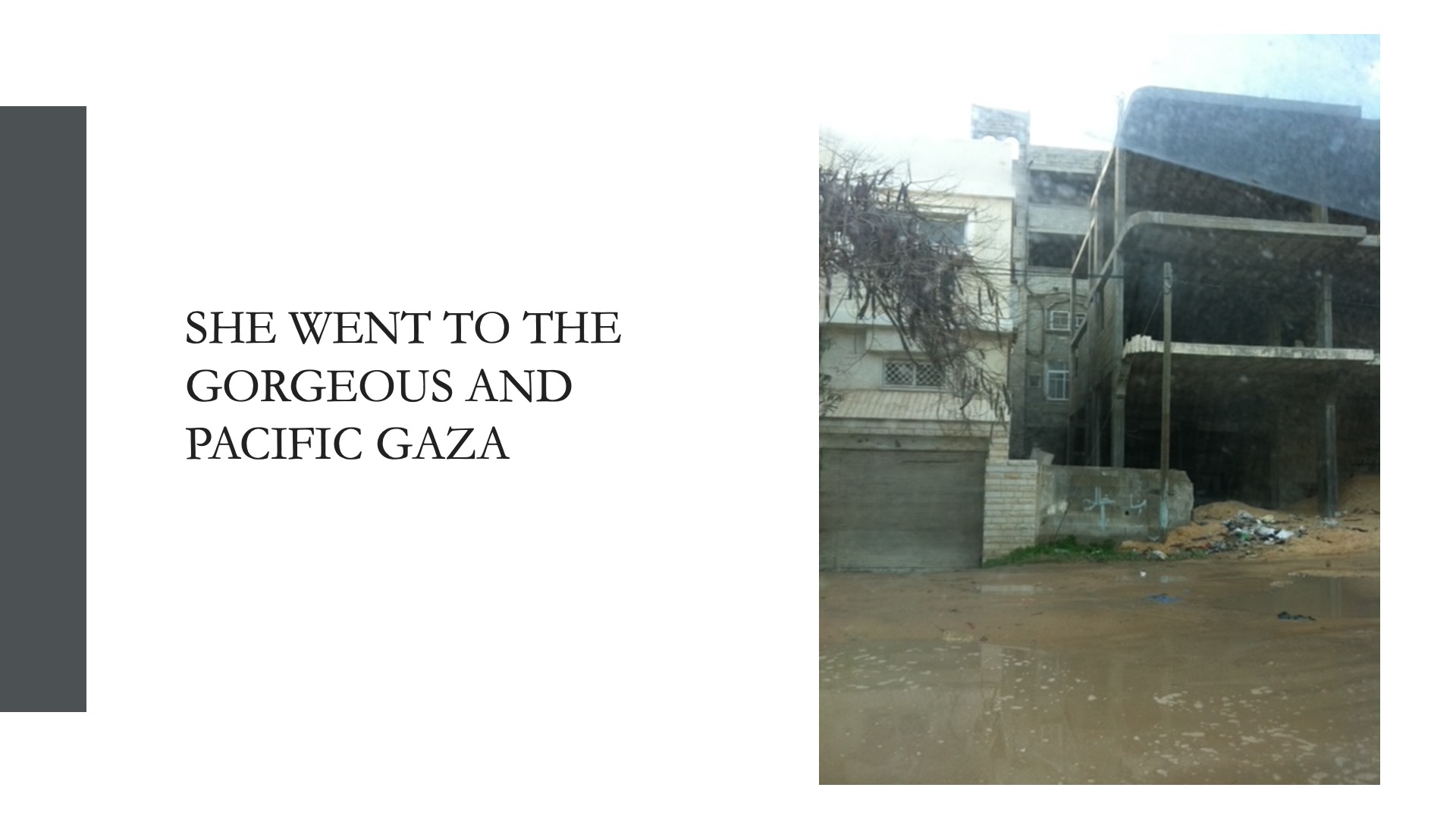

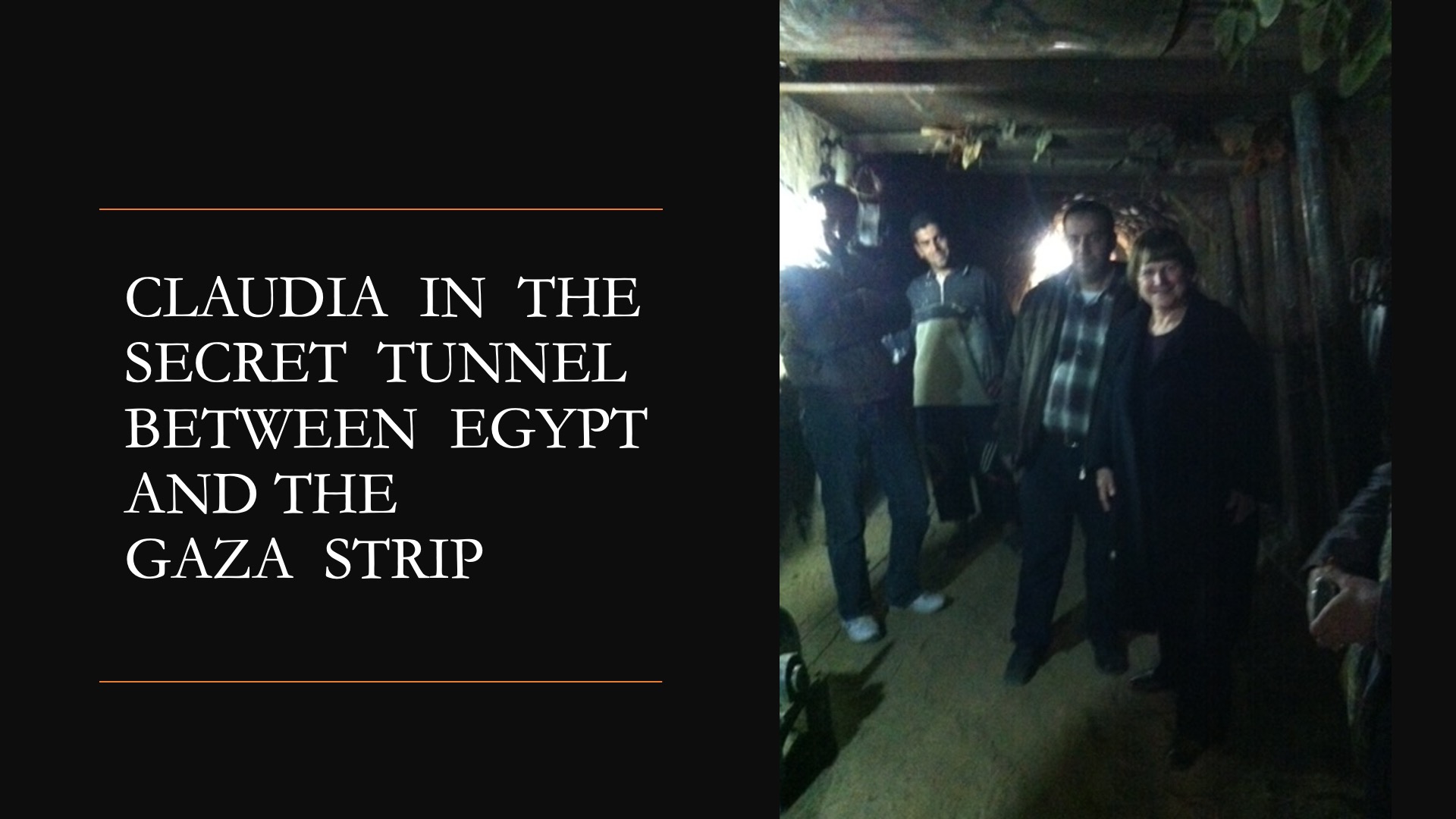

I’ll say it all: I’m with Claudia because she’s a completely globalised woman. ‘Globalised’ today is almost an insult, it immediately makes you think of bankers scattering their money around the world. Claudia is certainly cosmopolitan because she has travelled so much; it’s easier to list the countries she hasn’t visited than those she has. By cosmopolitan I mean a person who has no préjudices; not only religious or racial, I would say with no prejudices tout court. I have never heard her indulge in catchphrases, clichés, stereotypes about nations or people; for her everyone is above all a human being. Certainly, Claudia is not an intellectual – though I’m often surprised by how much knowledge she hides in the folds of her modesty. She is simply an intelligent person. Unfortunately, I know many stupid intellectuals. A natural consequence of intelligence is an allergy to clichés, to certain learned simplifications, to speaking like a printed book.

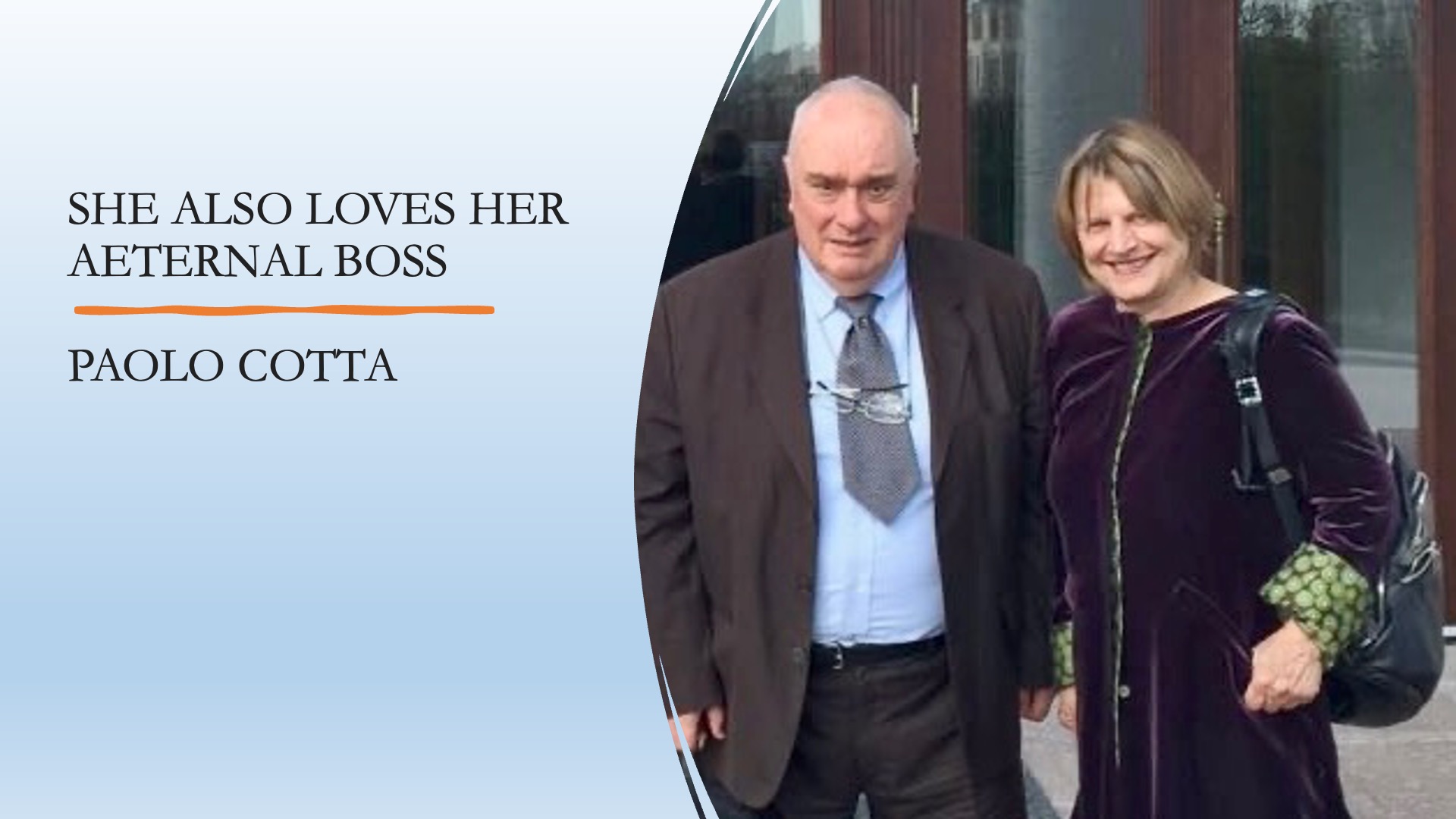

The Secretaries General of Pugwash have come and gone, but Claudia stays. Every new Secretary absolutely needs her, and not just because she knows the affairs of Pugwash like an architect knows everything about the building he or she has built. Claudia is indispensable because she knows how to make everyone feel at home. Claudia always assumes – an attitude she herself knows to be flawed – that every human being is good.

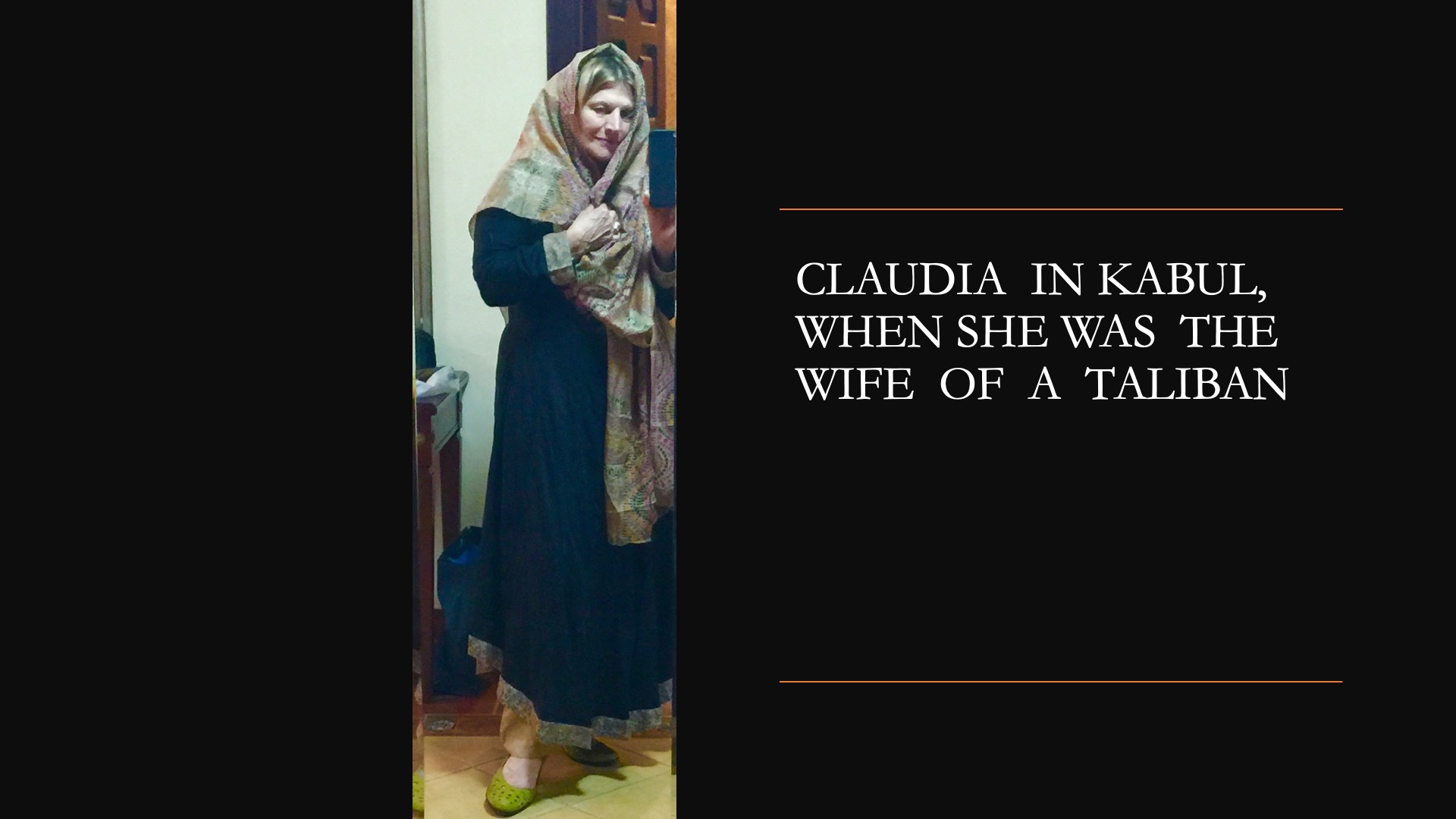

In fact, Claudia manages to feel comfortable with anyone, be it a Nobel laureate in Physics, a Russian hierarch, a Taliban, an active or retired terrorist, a spy, a historical feminist, an Arab prince... Because she lacks any sense of superiority towards anyone, even a drunken trump, she also lacks any sense of inferiority. I’m convinced that if she were introduced to Joe Biden, she would behave with him as she behaves with Giuliana, the pleasant poor country woman who is our neighbour in Montebuono, that is, in a welcoming way, with a smile, and she would say to him, “Can I be of any help, Joe?

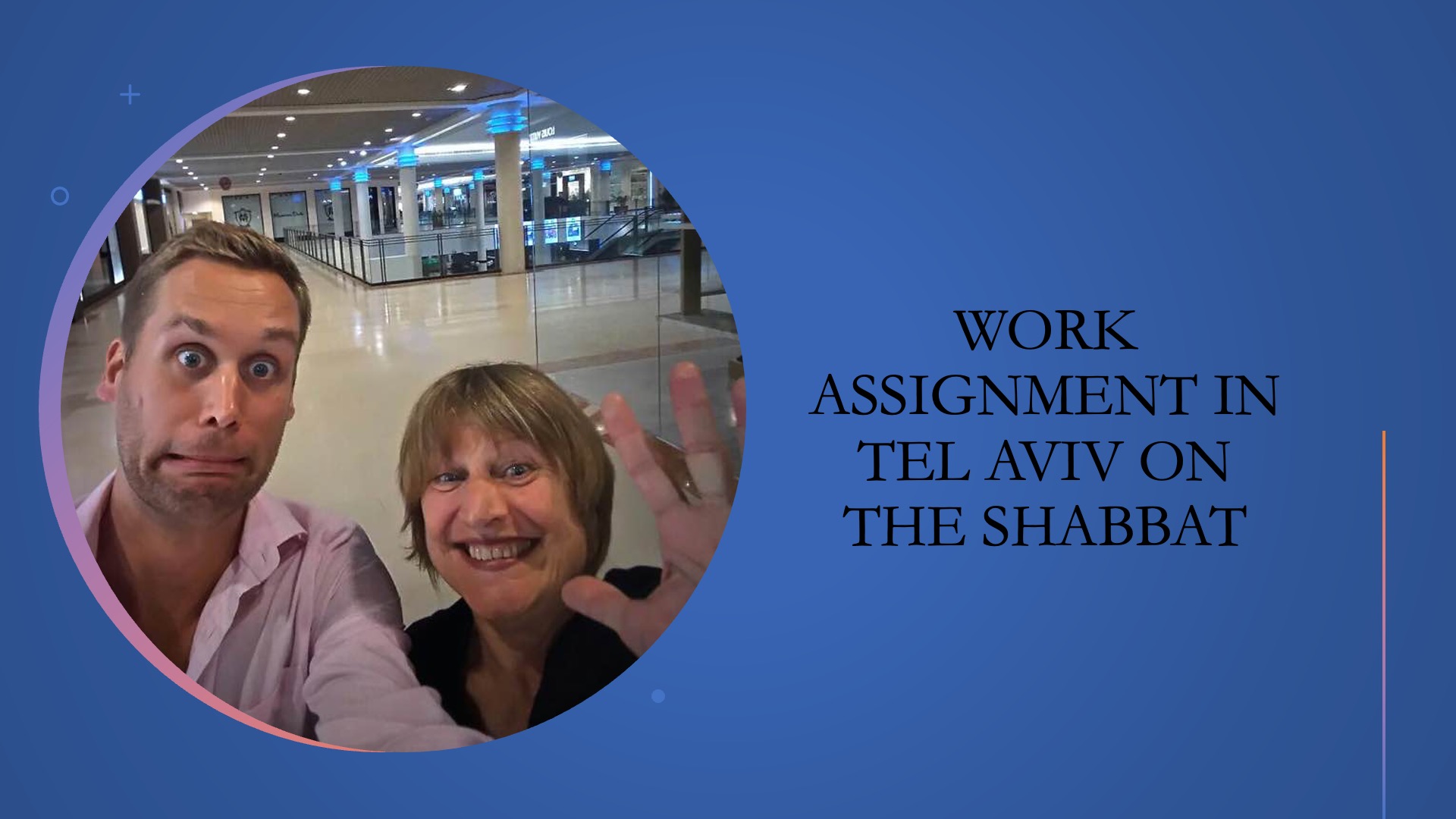

That’s it: “Can I be of any help?” Claudia is always ready to help, even strangers or near strangers. When a relative or friend asks her to be driven to an airport, Claudia never says no. Sometimes in Rome she meets foreign tourists from all sorts of countries and, if she likes them, spends the evening with them, maybe even pays for their dinner, and then goes out of her way to make their stay as pleasant as possible. Sometimes this generous benevolence seems excessive to me and I reproach her: “why do you drive people around or act as a tour guide for free?” And the answer she gives me is disarming: “Because I like it”. After all, Claudia only ever does what she likes. And it’s absolutely extraordinary that what she likes, someone else always likes too....

In short, Claudia is a good person, and that’s precisely why she’s happy. To be happy is above all to be good to yourself. But I know that this happiness is not something she was born with, far from it. It’s something she has achieved through an authentic ascesis, which as a philosopher, which I am in part, I envy her.

I’m about to reveal a secret, perhaps, something very few know about her... This joyful wisdom is the outcome of an early confrontation with death and despair. Sometimes she hears a voice inside her say, “They say she committed suicide!” Who committed suicide? And who are those who say it? In my opinion, Claudia, the old Claudia, committed suicide, and what she is, what she gives us, is what came out of this vanishing. She once told me “I’m a deeply melancholic person. And when you reach the very depths of mèlanchòly, it gives way to cheerfulness”. The cheerfulness of someone who has survived a tragedy.

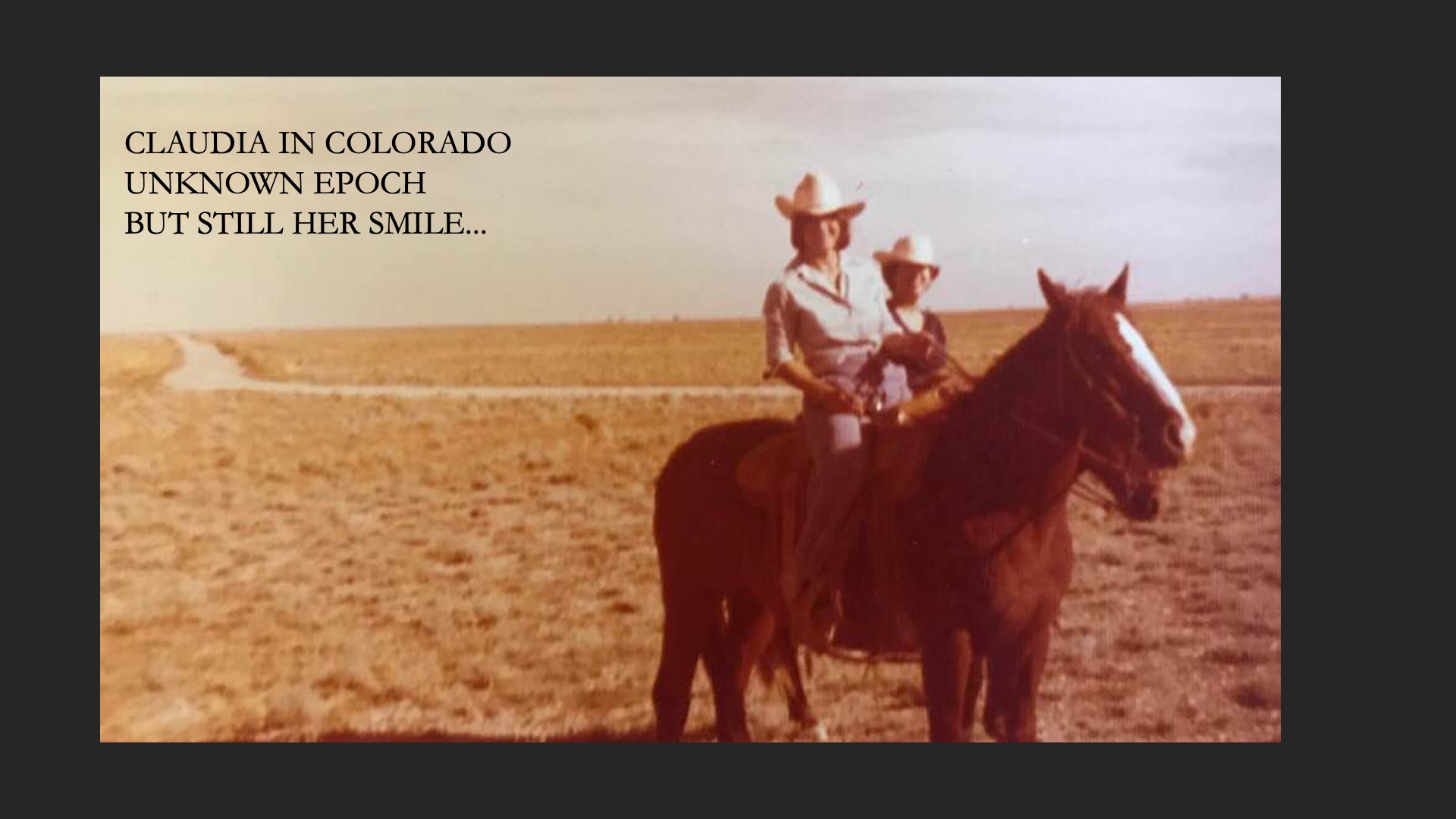

What tragedy? Perhaps that of her father, a veteran of the war in the Pacific? Of a father who survived two ship sinkings in the ocean, narrowly escaping being devoured by sharks or burned alive by the fuel from the wreckage? I don’t know. But Claudia has always been lucky enough to do jobs that give her pleasure, the job with Pugwash, and that allowed her to travel, to meet the most diverse people... Claudia, and myself after all, are basically nomads, adventurers. “I’m a quiet adventurer,” she once said. She confided in me that she used to dream of becoming the partner of an outlaw in the wild West. And she eventually found an outlaw like me. A woman of the hearth and a wanderer, but her hearth is not in space and time, it is in an indefinable place, what remains after sucking up the foam of the world.

Sometimes Claudia says she’s happy being in a couple with me, because I let her be alone. After all, ours is the union of two lonely singles. Single and married at the same time, it’s the best way to square the circle.

Claudia has the talent to console herself. For example, she has never complained about not having children, it’s enough for her to love our dog, Mila, now older than us. We love dogs because for us they are the very measure of humanity.

So, Claudia and I are growing old together, even though growing old is by no means pleasant; it’s abysmal in fact. But growing old with the one you love you can take comfort in your decline, because a collateral advantage of love is that in the one you love you see the freshness of youth behind the ludicrous mask of old age. The one you love only possesses an ageing body, but she is not. For me Claudia has even retained a childlike air, as if she always wanted to play blind man’s buff or ball. And when a carefree smile lights her up, I take joy in the glimpse of youth that that face coeval with mine restores to me. Love has the wisdom to infantilise the one you love. To look at the one you love is the opposite of looking at the portrait of Dorian Gray; it is the portrait that’s looking at you. In this way, Claudia even makes me feel young myself.

I think the key to understanding Claudia’s disenchanted cheerfulness is a scene she often describes, which goes back to the Cuban missile crisis when she was 14. In those days those who bet that nuclear war would break out between the US and the Soviet Union were almost sure to win. Schools, one day, had recommended that mothers prepare a backpack for their children with food and essentials that would allow them to stay away from home for seven days. in other words: “if the nuclear cataclysm strikes while your children are at school, they will need to survive at least a week in the shelter”. Claudia’s mother, apparently calm and confident, packed her daughter’s backpack with everything she needed. While Claudia turned away from this play acting and set off for school she couldn’t help looking back at the house that she would perhaps – she told herself deep down – never see again. She took leave of the house, the family and the world in silence, without crying; a silent leave-taking, an eternal leave-taking.

I know that the Claudia I’ve known is the Claudia who emerged from a nuclear cataclysm of the soul. I too am the remains of a cataclysm. Both of us are survivors who basically have nothing left to lose, who having lost everything feel free. I’m not referring to the loss of material goods; I’m talking about the loss of something to which we had unconsciously attached our lives. I would say that to authentically love we need to have lost something essential, to have happily survived. In old Naples they used to say “three are those who hold power: The Pope, the king, and he who has nothing”. Claudia, even more than me, has nothing, if not love. And love is the extraordinary power of those who have nothing.

Happy Birthday, Claudia

Sergio

When I was seven I fell into a depressive mood that led my parents to send me to a psychotherapist... I often cried at the thought that my paErents would die sooner or later. How could I have lived while they were dead? After many years I told myself that the reason for my precocious sadness lay elsewhere.

In fact, at that time, on the other side of the planet, in California, a little girl my age was suffering. The doctors had decided to remove one of her kidneys, which they did in Los Angeles, putting her in a children-only ward to which her parents had no free access. At the time, American doctors were as stupid as Italian doctors; they thought that parents would get in the way of their job of carving up children’s bodies... That child was Claudia. So, I often think: I must have known that the young girl who was to become my partner was suffering, separated from her parents. How could I not have known it? How could I not have feared death?

Claudia and I met late in life, when we were both 44; two months separate our births. The first time I went out with her, in Trastevere, I made a fool of myself. In a bar, when she asked me how old I was, I don’t know why, but I took a year off my real age; “43”, I said. But I soon gave myself away, because when Claudia asked me what my Chinese astrological sign was, I answered that I was a Mouse. “I’m a Mouse too,” she said. But Chinese astrological signs are determined according to the year of your birth. She forgave me the lie. Claudia always forgives everyone. Since then, however, I have stopped telling lies. Claudia has been my moral re-educator.

Claudia says that Americans are more ethical than Europeans at heart. Maybe she’s right, despite Trump and the Wolves of Wall Street. In fact, Claudia confessed to me one day that she has never lied. It’s impossible for her to lie; a lie would never come to her. Instead, she may omit certain important details. For example, when you ask her who she works for, she just says that she works for an obscure NGO that struggles for peace. She never says that this NGO was founded by Einstein and Russell and was awarded the Nobel Prize while she was working for it.

I began with Claudia aged 7, who was suffering, whose life was in danger. It’s the suffering side of Claudia that I would like to talk about here. Which is perhaps something scandalous, because everyone knows how radiant Claudia is, always cheerful, full of life. Claudia expresses a joie de vivre that does not carry the weight of the fear of death. She knows how to laugh even in tragedy. In 1993, as she told me that she had been diagnosed with cancer, which she would later defeat with a smile, she made the sign that in the Neapolitan language of gestures means going up to heaven; in other words, death: ------ She was mocking her illness.

I’ll say it all: I’m with Claudia because she’s a completely globalised woman. ‘Globalised’ today is almost an insult, it immediately makes you think of bankers scattering their money around the world. Claudia is certainly cosmopolitan because she has travelled so much; it’s easier to list the countries she hasn’t visited than those she has. By cosmopolitan I mean a person who has no préjudices; not only religious or racial, I would say with no prejudices tout court. I have never heard her indulge in catchphrases, clichés, stereotypes about nations or people; for her everyone is above all a human being. Certainly, Claudia is not an intellectual – though I’m often surprised by how much knowledge she hides in the folds of her modesty. She is simply an intelligent person. Unfortunately, I know many stupid intellectuals. A natural consequence of intelligence is an allergy to clichés, to certain learned simplifications, to speaking like a printed book.

The Secretaries General of Pugwash have come and gone, but Claudia stays. Every new Secretary absolutely needs her, and not just because she knows the affairs of Pugwash like an architect knows everything about the building he or she has built. Claudia is indispensable because she knows how to make everyone feel at home. Claudia always assumes – an attitude she herself knows to be flawed – that every human being is good.

In fact, Claudia manages to feel comfortable with anyone, be it a Nobel laureate in Physics, a Russian hierarch, a Taliban, an active or retired terrorist, a spy, a historical feminist, an Arab prince... Because she lacks any sense of superiority towards anyone, even a drunken trump, she also lacks any sense of inferiority. I’m convinced that if she were introduced to Joe Biden, she would behave with him as she behaves with Giuliana, the pleasant poor country woman who is our neighbour in Montebuono, that is, in a welcoming way, with a smile, and she would say to him, “Can I be of any help, Joe?

That’s it: “Can I be of any help?” Claudia is always ready to help, even strangers or near strangers. When a relative or friend asks her to be driven to an airport, Claudia never says no. Sometimes in Rome she meets foreign tourists from all sorts of countries and, if she likes them, spends the evening with them, maybe even pays for their dinner, and then goes out of her way to make their stay as pleasant as possible. Sometimes this generous benevolence seems excessive to me and I reproach her: “why do you drive people around or act as a tour guide for free?” And the answer she gives me is disarming: “Because I like it”. After all, Claudia only ever does what she likes. And it’s absolutely extraordinary that what she likes, someone else always likes too....

In short, Claudia is a good person, and that’s precisely why she’s happy. To be happy is above all to be good to yourself. But I know that this happiness is not something she was born with, far from it. It’s something she has achieved through an authentic ascesis, which as a philosopher, which I am in part, I envy her.

I’m about to reveal a secret, perhaps, something very few know about her... This joyful wisdom is the outcome of an early confrontation with death and despair. Sometimes she hears a voice inside her say, “They say she committed suicide!” Who committed suicide? And who are those who say it? In my opinion, Claudia, the old Claudia, committed suicide, and what she is, what she gives us, is what came out of this vanishing. She once told me “I’m a deeply melancholic person. And when you reach the very depths of mèlanchòly, it gives way to cheerfulness”. The cheerfulness of someone who has survived a tragedy.

What tragedy? Perhaps that of her father, a veteran of the war in the Pacific? Of a father who survived two ship sinkings in the ocean, narrowly escaping being devoured by sharks or burned alive by the fuel from the wreckage? I don’t know. But Claudia has always been lucky enough to do jobs that give her pleasure, the job with Pugwash, and that allowed her to travel, to meet the most diverse people... Claudia, and myself after all, are basically nomads, adventurers. “I’m a quiet adventurer,” she once said. She confided in me that she used to dream of becoming the partner of an outlaw in the wild West. And she eventually found an outlaw like me. A woman of the hearth and a wanderer, but her hearth is not in space and time, it is in an indefinable place, what remains after sucking up the foam of the world.

Sometimes Claudia says she’s happy being in a couple with me, because I let her be alone. After all, ours is the union of two lonely singles. Single and married at the same time, it’s the best way to square the circle.

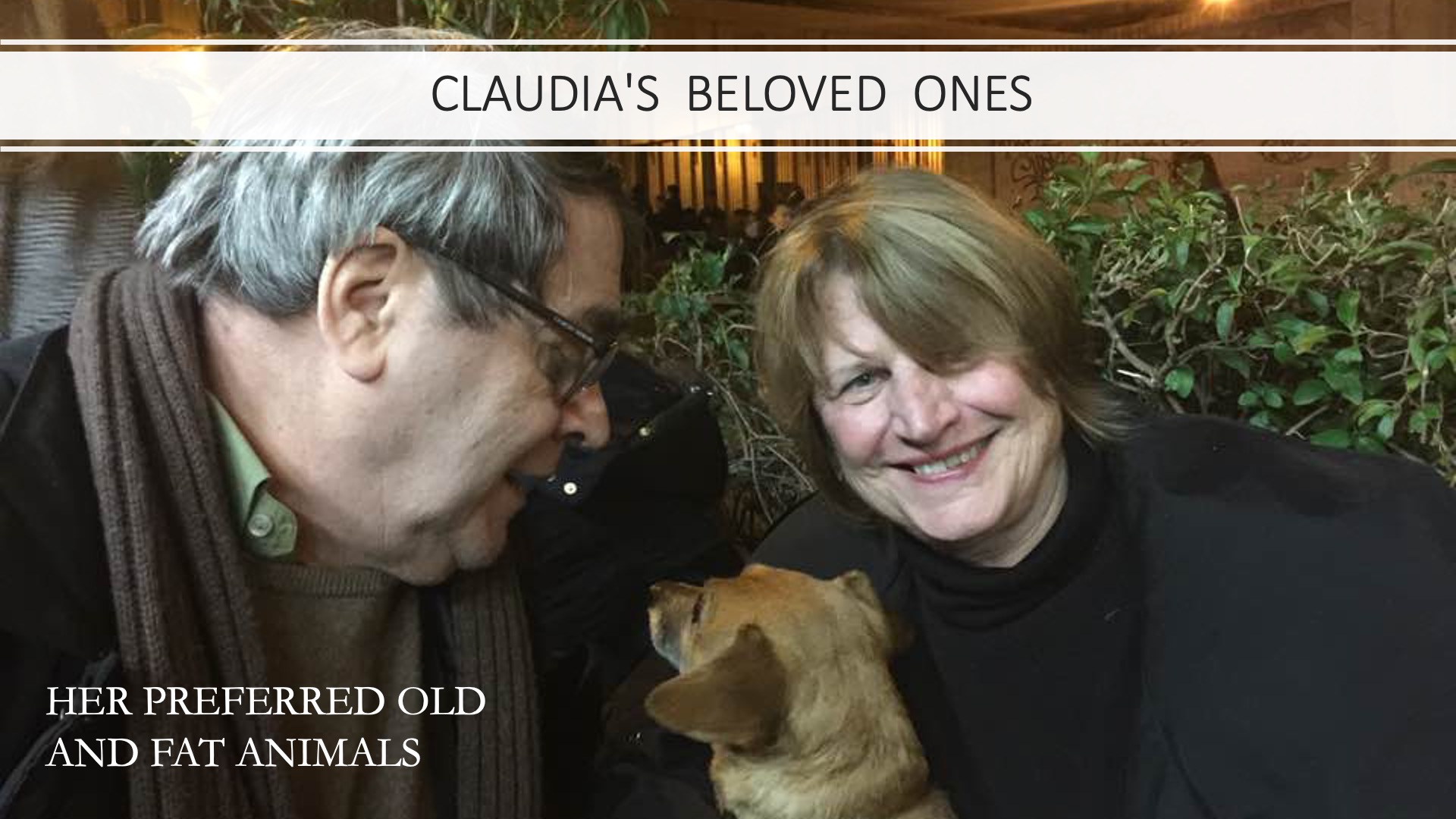

Claudia has the talent to console herself. For example, she has never complained about not having children, it’s enough for her to love our dog, Mila, now older than us. We love dogs because for us they are the very measure of humanity.

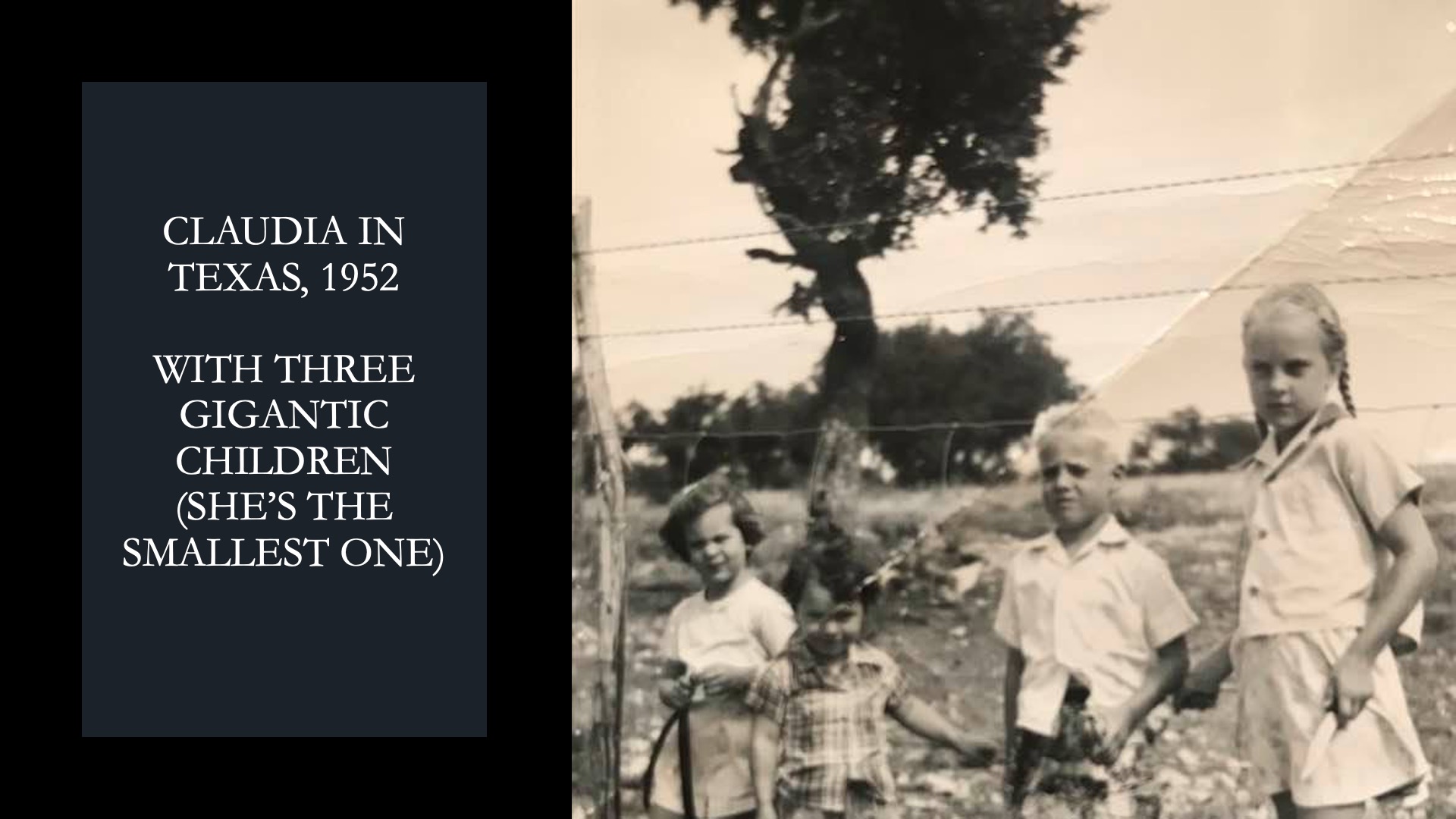

So, Claudia and I are growing old together, even though growing old is by no means pleasant; it’s abysmal in fact. But growing old with the one you love you can take comfort in your decline, because a collateral advantage of love is that in the one you love you see the freshness of youth behind the ludicrous mask of old age. The one you love only possesses an ageing body, but she is not. For me Claudia has even retained a childlike air, as if she always wanted to play blind man’s buff or ball. And when a carefree smile lights her up, I take joy in the glimpse of youth that that face coeval with mine restores to me. Love has the wisdom to infantilise the one you love. To look at the one you love is the opposite of looking at the portrait of Dorian Gray; it is the portrait that’s looking at you. In this way, Claudia even makes me feel young myself.

I think the key to understanding Claudia’s disenchanted cheerfulness is a scene she often describes, which goes back to the Cuban missile crisis when she was 14. In those days those who bet that nuclear war would break out between the US and the Soviet Union were almost sure to win. Schools, one day, had recommended that mothers prepare a backpack for their children with food and essentials that would allow them to stay away from home for seven days. in other words: “if the nuclear cataclysm strikes while your children are at school, they will need to survive at least a week in the shelter”. Claudia’s mother, apparently calm and confident, packed her daughter’s backpack with everything she needed. While Claudia turned away from this play acting and set off for school she couldn’t help looking back at the house that she would perhaps – she told herself deep down – never see again. She took leave of the house, the family and the world in silence, without crying; a silent leave-taking, an eternal leave-taking.

I know that the Claudia I’ve known is the Claudia who emerged from a nuclear cataclysm of the soul. I too am the remains of a cataclysm. Both of us are survivors who basically have nothing left to lose, who having lost everything feel free. I’m not referring to the loss of material goods; I’m talking about the loss of something to which we had unconsciously attached our lives. I would say that to authentically love we need to have lost something essential, to have happily survived. In old Naples they used to say “three are those who hold power: The Pope, the king, and he who has nothing”. Claudia, even more than me, has nothing, if not love. And love is the extraordinary power of those who have nothing.

Happy Birthday, Claudia

Sergio

IT

IT OTHER LANGUAGES

OTHER LANGUAGES